Executive Summary:

- A June 27 joint proposal by the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC to lower the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR), a capital constraint on large banks, aims to remove regulatory disincentives to Treasury security intermediation.

- While myriad studies and analyses conclude that the eSLR disincentivizes intermediation, removing these constraints equally benefits competing low-risk activities that may offer higher returns.

- Banks may deploy freed capital toward higher-yielding activities rather than Treasury intermediation, potentially undermining the rule’s intended purpose.

Introduction:

On June 27, the Federal Reserve (Fed), FDIC, and OCC posted a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), with the intention to lower the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio (eSLR). A standard SLR is a ratio (3 percent) that requires banks to hold capital equal to a fixed percentage of outstanding assets, regardless of the risk associated with those assets. The eSLR currently adds a 2 percent buffer to this ratio, for the largest 8 U.S. banks (G-SIBs). The proposed rule will lower the eSLR by roughly 1.4 percent for G-SIBs and their subsidiaries. The respective banking agencies’ regulatory analysis for this proposed rule states the rule would “reduce disincentives for banking organizations to participate in U.S. Treasury market intermediation.” Treasury intermediation is a vital part of a healthy economy, where banks act as middlemen for the purchase and sale of Treasury securities with investors. However, while Treasury intermediation represents one option for banks, the rule provides no mechanism to ensure banks prioritize it over other equally low-risk activities that may offer superior returns. Although leverage ratios do constrain Treasury intermediation, it remains uncertain whether banks will favor it over other equally low-risk but higher-yielding opportunities.

Understanding the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking:

The exact framework of the rule is complex in design, as eSLRs will vary by bank. However, G-SIBs will see leverage ratios 1.4 percentage points lower on average. As Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell notes at the beginning of his statement on the rule: “We want to ensure that the leverage ratio does not become regularly binding.” Figure 1 shows how G-SIBs’ leverage ratios have declined over time and are approaching the 5% regulatory threshold (red dotted line), with some banks already hitting this constraint. The diamonds indicate instances where the eSLR becomes the binding regulatory constraint rather than the traditional risk-based capital requirements, demonstrating that this leverage rule is increasingly affecting these banks’ operations.

Figure 1: eSLR Over Time for G-SIBs

Source: Dealers’ Treasury Market Intermediation and the Supplementary Leverage Ratio

Within the regulatory analysis, respective agencies estimate that G-SIB parent banks would only be able to lower reserves by $13 billion total (less than 2 percent of capital). Comparatively, subsidiaries are estimated to be able to free up balance sheet space by $213 billion (27 percent) in the aggregate. The agencies involved in this proposed rule write that leverage ratios, “under certain circumstances, impede the orderly functioning of the U.S. Treasury market.”

To avoid this regulatory impediment, these agencies believe lowering the eSLR will help alleviate pressures on the Treasury market. Subsequently, these banking agencies believe removing these constraints will allow banks to resume Treasury market participation. But is there actually any evidence of this relationship?

The Uncertain Path of Freed Capital:

When an investor finds $100 on the ground, they do not put that money in their 2% interest savings account; they look for higher-yield opportunities. If regulators give banks additional capital allocation, would they use it for Treasury intermediation? It depends on the relative yields of other opportunities.

Banks reap profits from Treasury intermediation by buying securities and then selling them to customers at a higher price. Banks profit more on intermediation when yields are higher, through an increase in securities demanded, higher yields for held securities, and increased repo activity. With yields currently averaging 4.34 percent across all maturities, will banks see this as high enough to ensure they are getting value out of Treasury intermediation? If not, they will take this new capital allocation that has been granted to them and spend it elsewhere, on higher-yielding operations.

Freed capital could instead flow toward cash-collateralized lending or direct holdings of government-guaranteed securities. These activities carry identical risk weights but can generate higher yields than Treasury market intermediation, depending on market circumstances.

Crucially, lowering the eSLR removes constraints not just for Treasury intermediation, but for all low-risk activities equally. Cash-collateralized lending, direct holdings of government-guaranteed securities, and other similar activities face the same regulatory relief. Banks will rationally allocate freed capital to whichever of these newly-available options offers the highest returns, with Treasury intermediation competing alongside these alternatives rather than being the default beneficiary of regulatory relief.

Questionable Evidence from Unprecedented Times:

Within the NPRM for this deregulatory action, agencies cite a plethora of previous literature to back their economic analysis.1 These papers generalize to the conclusion that increases or binding of the leverage ratio hinder a bank’s ability to participate in low-risk Treasury intermediation. However, with a lack of precedential policy on the topic, authors note that “establishing a causal channel from the SLR requirements to Treasury market participation is challenging….”

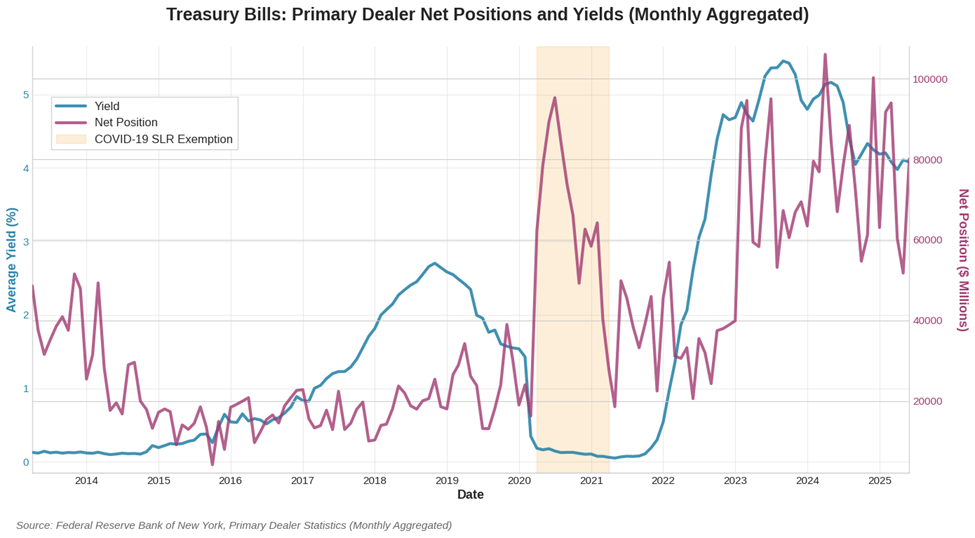

Consequently, much of the literature explicitly cited by these regulatory agencies focuses conclusions on evidence from a similar ruling during COVID-19, though this analysis has limitations. During COVID-19, the Fed decided to exempt Treasury securities from the denominator of leverage ratios. Although this closely matches the intention of the current rulemaking, the exemption was implemented during one of the most volatile market instances in history. Figure 2 plots both the primary dealer net positions (e.g., Treasury securities, bills in this case, held by banks) and yields for the respective maturity. This chart shows how much Treasury debt banks were holding over time alongside the interest rates those securities were paying.

Figure 2: Primary Dealer Net Positions and Yields

Source: New York Fed

Intuition from Figure 2 points to the exemption period causing these shifts in positions. However, determining causation is challenging. On the exact date the exemption went into effect, the Fed bought $1 trillion in Treasury securities from banks, freeing up balance sheet space. Additionally, securities across all buyers and sellers saw unprecedented movement in March 2020, the same month this exemption went into effect. This evidence fails to demonstrate that loosening leverage ratios incentivizes Treasury intermediation.

Dissenting Voices Within the Fed:

This ambiguity is not lost on Fed officials. When Principal Economist Akos Horvath was asked what empirical evidence shows about loosening SLRs, Horvath responded, saying empirical evidence shows that “banks (broker-dealers) whose holding companies have lower SLRs are more reluctant to engage in U.S. Treasury market intermediation and participate in the U.S. Treasury market in general.”

Governor Barr echoes these concerns in his dissenting statement, arguing that “firms could just as easily shift to other activities with low risk-based capital requirements and significantly higher returns than Treasury market intermediation.”

Governor Kugler, who also dissented, took a different approach by focusing on the risk-benefit analysis. Rather than questioning whether the rule would work, Kugler’s statement argued that “ultimately [it would] increase systemic risk in a manner that is not justified by the benefits cited in the proposal.” Barr and Kugler were the only Governors to dissent on the ruling during the Fed’s June meeting.

These internal concerns align with the broader issue identified earlier, that freed capital may flow toward higher-yielding activities rather than the low-margin Treasury intermediation the rule aims to support. Moreover, if the rule fails to alleviate pressures on Treasury intermediation as intended, systemic risk will be introduced into the largest U.S. banks without any corresponding benefit.

Conclusion:

While lowering the eSLR appears well-intentioned, the proposed rule rests on inadequate empirical evidence and flawed assumptions about bank behavior. By removing regulatory constraints broadly across all low-risk activities, the rule creates equal opportunities for Treasury intermediation and its higher-yielding competitors alike. The limited proof that removing constraints will direct freed capital specifically toward Treasury intermediation rather than competing alternatives, combined with contradictory statements from Fed officials, suggests this effort may backfire entirely. Without strong evidence to support such an effort, the rule threatens to allow non-value-added risk to permeate through the U.S. banking industry. In such circumstances of limited information, regulators should take a more cautious approach, not only to this rule, but also to regulation as a whole. Ultimately, it will be incentives, specifically relative yields, that determine whether banks will use this freed capital for intermediation or seek profits elsewhere.

Footnotes:

- (Andersen et al. 2019, Du et al. 2018, Correa et al. 2020, Duffie 2020, Fleckenstein & Longstaff 2020, Cenedese et al. 2021, He et al. 2022, Du, Hebert & Li 2023, Du, Hebert & Huber 2023, Eisenbach & Phelan 2023, Infante & Saravay 2023, Allen & Wittwer 2024). ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.