Executive Summary

- On September 19, California Governor Gavin Newsom approved a bill renewing California’s cap-and-trade program until 2045.

- This decision comes despite hostility toward state-level clean energy programs from the Trump administration, notably President Trump’s executive order that specifically criticized California’s cap-and-trade program.

- California’s cap-and-trade system has driven significant emissions reductions and generated billions in revenue for additional environmental and community projects, but overallocated allowances, carbon leakage, and continued federal challenges to the program may weaken the carbon price signal’s efficacy in the future.

Introduction

On September 19, California Governor Gavin Newsom approved a bill renewing California’s cap-and-trade program until 2045. The program, previously set to expire in 2030, was the first economy-wide cap-and-trade system in North America and is one of several initiatives aimed to help California achieve some of the most ambitious state-level climate goals in the country.

This renewal comes despite hostility towards state-level clean energy programs from the Trump administration. In April, President Trump issued an executive order titled “Protecting American Energy from State Overreach,” calling out California’s cap-and-trade program for setting “radical requirements” and “impossible caps” on carbon-intensive businesses. This criticism reflects Trump’s broader energy dominance agenda, pushing America to be at the forefront of fossil fuel production while halting clean energy initiatives.

Despite this federal affront, California doubled down on its commitment to the market-based climate policy. This tension between California and the federal government raises pertinent questions about the achievability and effectiveness of California’s emissions caps. This insight explores whether California’s cap-and-trade system delivers an effective carbon price signal to reach its ambitious climate goals and if California’s compliance obligations are achievable for regulated entities.

Cap-and-Trade Mechanism

California’s cap-and-trade program was unique in that it set out to regulate carbon emissions by leveraging market-based incentives across multiple sectors, including power, industry, transportation, buildings, and agriculture, altogether targeting around 80 percent of California’s total emissions for reduction. This is different from the pre-existing Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) in the eastern United States, which enforced cap-and-trade only on the power sector.

California’s cap-and-trade program is managed by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), who sets annual emission limits, or “caps,” for entities exceeding 25,000 metric tons of CO₂ equivalent emissions per year. More specifically, CARB directly allocates allowances to regulated entities. One allowance permits an entity to emit one metric ton of CO₂ equivalent. CARB also sells allowances in quarterly auctions, where participants can buy additional allowances to ensure that they have enough to cover their emissions for a compliance period, typically three years. Regulated entities may use their acquired allowances to satisfy their compliance obligations, bank them for use in a future compliance period, or sell them to other entities in a secondary market.

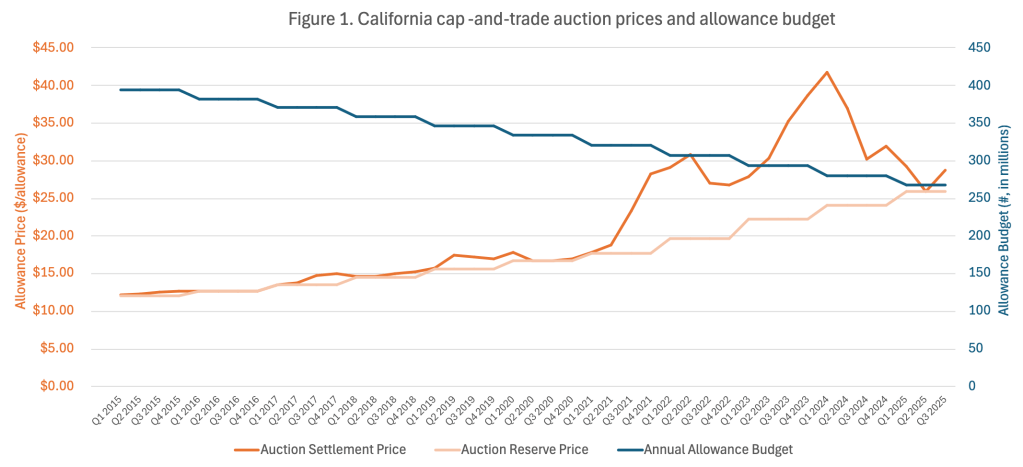

Each year, CARB decreases the total number of allowances distributed, incrementally forcing a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions over time. CARB also increases the annual auction reserve (floor) price each year. The combination of increasing floor prices and decreasing number of distributed allowances creates a carbon price signal that prompts regulated entities to invest in cleaner technologies and reduce their GHG emissions.

Source: California Air Resources Board

Brief History

California has ambitious statutory emissions goals, aiming to hit 1990 emission levels by 2020 (achieved in 2016), 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, and 85 percent below 1990 levels by 2045. One initiative aimed at meeting these targets is the cap-and-trade program, which was authorized by the 2006 Global Warming Solutions Act. In 2012, CARB conducted its first allowance auction. The following year, compliance obligations for GHG emissions began for electricity generators and large industrial facilities. In 2015, the program expanded to additional sectors, adding compliance obligations to distributors of transportation fuels, natural gas, and other fuels.

The cap-and-trade program faced legal challenges since its early years, on the basis that CARB did not have the authority to run auctions, generate revenue, and create market-based compliance. In 2019, the first Trump administration sued the state of California for its cap-and-trade program on the basis that its linkage with Quebec’s cap-and-trade system was an illegal international agreement.

The program has survived all lawsuits so far. Originally set to expire in 2020, the program was extended through 2030 in 2017. The program was once again extended through 2045 in September 2025 while renaming it California’s “Cap-and-Invest Program.” The rebranding aimed to emphasize that the revenue generated from the program, amounting to $33 billion as of 2024, would be used to further fund carbon-reduction initiatives.

Assessing Policy Effectiveness

Carbon Price Signal

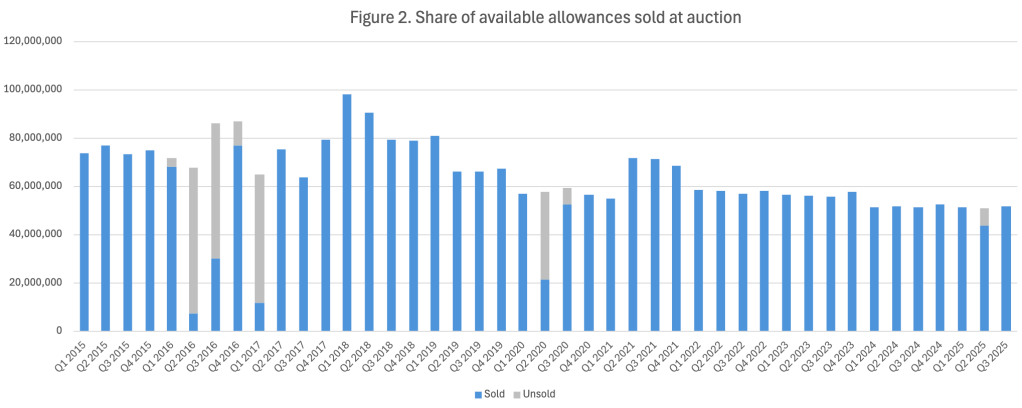

Figure 2 shows a record of the portion of allowances sold in each allowance auction since 2015. In most auctions, 100 percent of the offered allowances were sold, with the exception of auctions between 2016 and early 2017, in 2020, and in 2025, where the supply of allowances was greater than the demand.

Source: California Air Resources Board

The presence of surpluses in the market indicates that the system overallocated allowances and set weak emission caps in the market. The auction settlement prices (Figure 1) further confirm that the market mechanism was weak in periods with allowance surpluses. Every auction with a surplus of allowances coincided with a settlement price exactly equal to the floor price, and secondary market trades occurred at prices below the floor. This signifies weak demand and limited competition for allowances between regulated entities. Shortly put, there was little incentive for regulated entities to purchase allowances during these periods.

There are two factors that could explain surplus auctions. First, regulated entities may have exceeded expectations and developed cleaner technologies faster than CARB anticipated, lowering demand for allowances. On the other hand, it could also reflect a lack of confidence in the longevity of the cap-and-trade system. Interestingly, the surpluses in 2016-2017 occurred concurrently with a lawsuit by the California Chamber of Commerce challenging the cap-and-trade program and a U.S. Supreme Court order to suspend the enforcement of the Clean Power Plan. Uncertainty about whether the compliance obligations would remain in future years could have prompted regulated entities to hold off on purchasing allowances.

Allowance demand recovered in mid-2017, partly due to the resolution of legal challenges to the system and regulatory adjustments. Since then, the pricing system has remained largely stable, evidenced by the maximum allowances consistently selling in auctions and settlement prices rising above the floor price. The only two deviations occurred in 2020 and 2025—the former likely due to slowed industrial activity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the latter potentially reflecting uncertainty surrounding federal challenges to state-level climate policies. Both deviations, however, appear to be short-term anomalies and not reflective of a broader trend. In general, the California cap-and-trade program seems to have created an effective carbon price signal, despite temporary disruptions caused by unprecedented external factors.

Emissions Reduction

Based on the state’s 2022 Scoping Plan, the cap-and-trade program is expected to drive a 22 percent decrease in greenhouse gas emissions through two mechanisms: First, it forces regulated entities to decrease their carbon emissions by sending price signals in the cap-and-trade market. Second, the revenue generated from the cap-and-trade markets is reinvested into emission-reduction projects.

CARB decreases the number of allowances released to regulated entities every year, which is intended to ensure a reduction in emissions from major polluters over time so that California’s emissions targets can be met. So far, the system seems to have the intended consequences. In fact, reported emissions from regulated entities have remained below the annual allowance budget set by CARB, shown in Figure 3.

Source: California Air Resources Board

However, the allowance budget is not equivalent to the emission limit for a given year, since entities have the option to bank their allowances, saving them for future compliance periods. As of 2021, over 300 million allowances have been banked, double the number that was projected by CARB in 2018. While it’s possible that some regulated entities have developed clean technologies that place them on a decarbonization trajectory where they won’t have to use their banked allowances, there is a risk that regulated entities will use their accumulated allowances in the future without further investing in emissions reduction. Essentially, an accumulation of banked allowances weakens the future scarcity of allowances that is critical for incentivizing regulated entities to reduce emissions.

The revenue generated by cap-and-trade auctions goes into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), which is used to pursue environmental solutions and support disadvantaged and low-income communities across California. Of the $33 billion generated by the cap-and-trade system, $18.4 billion has been committed to funding over half a million projects, with $12.8 billion having been implemented so far. Some of the major projects undertaken with cap-and-trade dollars include investing in a high-speed rail project, supporting affordable housing and sustainable communities, and protecting air quality. These environmental and community-oriented projects funded by GGRF have contributed to 116.1 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent greenhouse gas emission reductions.

It is difficult to isolate the effects of the cap-and-trade program on California’s emissions from their other climate initiatives, such as renewable portfolio standards and vehicle emission regulations. However, since the program began, California has experienced a 14 percent decline in greenhouse gas emissions, indicating that its climate policies are on the right track to hitting their ambitious goals.

External Considerations

In implementing a carbon price, cap-and-trade raises costs for producers in California, both by requiring allowance purchases in auctions and driving investing in clean technologies. These additional costs may put regulated entities at a competitive disadvantage to those operating outside of California. Carbon border adjustments are a mechanism aimed at preventing carbon leakage, where producers shift their operations to areas with less stringent carbon constraints. Border adjustments include taxes on imports and rebates on exported goods.

The 2006 Global Warming Solutions Act that established the cap-and-trade program required reductions on any electricity consumed inside of California, including its imported electricity supply. As a result, electricity importers in California were subject to carbon pricing since the start of the program, but similar policies do not yet exist for other sectors. However, the legislation that renewed the cap-and-trade program to 2045 also required CARB to report an assessment of emissions leakage, including an exploration into further carbon border adjustment measures by December 2025.

Controlling carbon leakage through border adjustments will certainly introduce administrative complexities, since it becomes necessary to calculate and report emissions associated with each product. However, ensuring that California and out-of-state producers face comparable carbon prices is critical. Otherwise, regulated entities may relocate their operations outside of California, and the emissions reductions achieved in California could be offset by increased emissions elsewhere, undermining the purpose of the cap-and-trade program.

Conclusion

Despite Trump’s criticism that California’s cap-and-trade program set “impossible” standards, regulated entities have met and exceeded CARB’s benchmarks for over a decade. Further, the program’s carbon price signal and auction revenues have effectively driven emissions reductions across sectors. It remains to be seen whether the program’s success will be sustained so that California can reach its carbon neutrality goal by 2045.

The approximately 300 million banked allowances present a risk, as they provide regulated entities the opportunity to slow or halt investment in clean technologies and continued emissions reduction, and instead resort to using their saved allowances to meet future compliance obligations. Additionally, carbon border adjustments should be thoughtfully considered to ensure that the carbon price signal is applied fairly to both California and out-of-state producers, preventing emissions leakage while upholding California producers’ economic competitiveness. Lastly, continued federal challenges to California’s cap-and-trade system may pose threats. Since Trump’s executive order, federal lawsuits have already targeted climate initiatives in New York, Vermont, Hawaii, and Michigan. Hypothetically, a lawsuit against California’s cap-and-trade program could erode confidence in the program’s longevity, as seen in 2016, leading to declining auction prices and weakening the carbon price signal that incentivizes polluters to invest in cleaner technologies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.