Executive Summary

- While China is reaping the benefits of entering the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – the world’s largest free trade agreement (FTA) – the United States has not established a competitive FTA of its own in the Indo-Pacific.

- RCEP’s tariff schedule aims to reduce tariffs for RCEP nations by approximately 92 percent over the next 20 years, granting countries including Japan, Australia, and South Korea essentially open-market access to China.

- China’s trade value with RCEP nations has increase by 7.5 percent in 2022, and by failing to sign a similar trade agreement, the United States risks limiting its economic growth while encouraging Indo-Pacific countries to be more reliant on China.

Indo-Pacific Trade Agreements

The Indo-Pacific’s premier trade agreement is RCEP, which includes 15 countries spread throughout Southern Asia, Eastern Asia, and Oceania. RCEP is the world’s largest trade agreement on many fronts, boasting a 28 percent share of global goods trade in 2020.

Source: Congressional Research Service

RCEP’s primary goal is establishing a deeper connection between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – whose largest members by 2022 gross domestic product (GDP) are Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore – with five of its FTA partners: China, Japan, Australia, South Korea, and New Zealand. RCEP features a tariff schedule which reduces tariff-based trade barriers, meaning trade markets between RCEP countries open gradually over time. Over the next 20 years, the nations have agreed to reduce or eliminate tariffs by approximately 92%, signaling increasingly deeper integration between China and its RCEP trading partners.

RCEP’s impact is already evident, especially for China, whose trade with ASEAN has increased 64% from 2017-2022. A 2020 Peterson Institute study estimated RCEP could add approximately $500 billion to global trade over the next two decades, with over $240 billion of that involving China. In 2022, S&P Global predicted RCEP’s share of global exports will grow to approximately 34% in 2040, three times the export share of the Canada-United States FTA.

The United States is taking a different approach to Indo-Pacific engagement through an economic framework, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF). IPEF was launched in May of 2022, and focuses on building connected, resilient, clean, and fair economies. Although, IPEF – contrary to RCEP – is not a formal trade agreement. IPEF’s stated aim is to “deepen United States economic engagement” in the Indo-Pacific, but it is not focused on negotiating tariff cuts. IPEF is instead raising regulatory standards in the region, a non-tariff barrier that may discourage U.S. Indo-Pacific trade.

Research by the Asia Society Policy Institute reports that many Indo-Pacific countries “would prefer to align more closely with the United States, but they remain disappointed with Washington’s declining interest in trade agreements.” The United States may not be able to compete with China in the Indo-Pacific if China is offering lower tariff barriers to almost all the United States potential trading partners. IPEF is an agreement between the United States, 11 RCEP countries, Fiji, and India. Therefore, most of the United States IPEF partners are also members of RCEP and will benefit from the comprehensive tariff schedule offered by China over the next two decades.

Tariff Schedules

RCEP’s tariff schedules will result in near open-market access for its members, meaning prices charged by an exporting business will essentially reflect prices paid in the importing country. While import tariffs are taxes paid by importing firms and consumers, lower tariffs are attractive to exporters, who benefit from their goods being competitively priced on international markets. RCEP’s tariff schedules boast diminishing tariff barriers, encouraging increased trade among its nations. IPEF has no such feature, and U.S. Indo-Pacific tariffs will remain stagnant if the status quo holds. While Chinese markets are not currently as open as U.S. ones, Chinese markets are liberalizing rapidly for RCEP members. In two especially interesting cases for Japan and South Korea, Chinese tariff-based trade barriers are scheduled to drop below those offered by the United States, resulting in freer access to Chinese markets than American ones for the first time in modern history.

Sources: World Integrated Trade Solution, RCEP Text

While China, Japan, South Korea, and the other RCEP nations are lowering trade barriers for each other, the United States does not seem interested in cutting tariffs. The Biden Administration is not expected to open foreign markets by reducing tariffs, and the former Trump administration implemented numerous protectionist policies, an idea that candidate Trump continues to support.

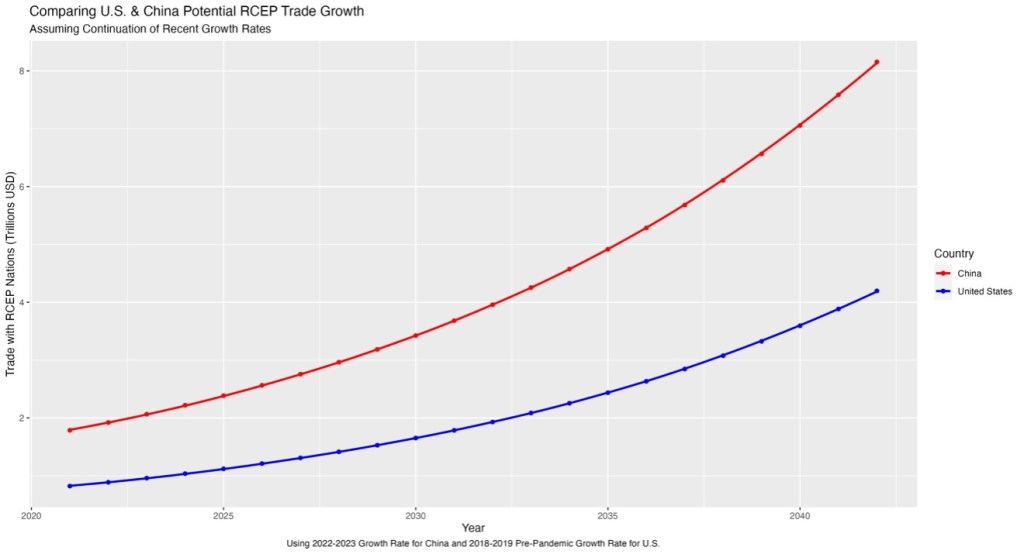

Trade Growth

Since RCEP entered into force in 2022, the FTA has been incredibly successful for China. Trade between China and other RCEP member countries increased 7.5% in the agreement’s first year alone. While the United States has historically been increasing trade in the Indo-Pacific over the last decade, the implementation of RCEP’s tariff schedule may lead to the United States falling behind in the region’s trade activities. Even if the United States were to continue Indo-Pacific trade at a pre-pandemic growth rate of 8.1 percent (2018–2019), if China were to continue the 7.5% growth it experienced in RCEP’s first year, Chinese total trade with its RCEP partners would surpass $7 trillion in 2040, while U.S. trade with the same countries would only amount to $3.6 trillion (in current U.S. dollars).

Sources: China SCIO, World Integrated Trade Solution

These simple calculations provide a baseline estimate, but RCEP’s attractive tariff schedule may lead to exponential Chinese trade growth, creating an even greater divide in the two largest economies’ Indo-Pacific involvement. Additionally, if the White House were to implement more protectionist policies such as Trump’s proposed 10% tariff, the U.S. may risk a decline in Indo-Pacific trade growth, which would also suggest a greater divide between Chinese and U.S. involvement in the region.

While still developing, many of RCEP’s countries have seen incredible economic growth and increasing influence in global trade markets during recent decades. If this trend continues, RCEP – already the world’s largest trade agreement – may continue to rise in global influence at the expense of the United States.

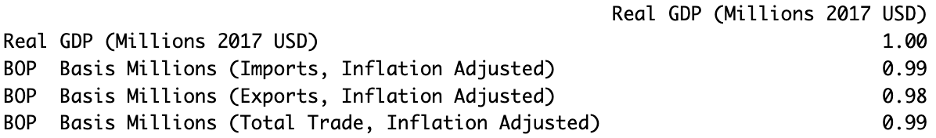

Currently, RCEP’s scheduled evolution seems increasingly beneficial to Chinese trade growth, while IPEF’s vagueness seems ineffective for the growth of U.S. trade. Considering the near-perfect correlation (detailed below) between trade value and real GDP in the United States (1960–2022), failing to alter American Indo-Pacific trade policies could be detrimental to U.S. economic growth.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, FRED

Conclusion

RCEP is providing a platform for rapid trade growth between China and other Indo-Pacific nations. The United States response in IPEF may be incomplete and does not currently lower trade barriers between the United States and the Indo-Pacific. The Chinese already have – or are scheduled to – lower tariff-based trade barriers below American levels for all RCEP countries, including important trading partners such as Japan and South Korea. The resulting freer access to Chinese markets could encourage Indo-Pacific countries to favor trade with China over the United States. By failing to adjust its Indo-Pacific trade policy, the United States risks passing up significant trade opportunities, potentially harming U.S. economic growth and encouraging RCEP members to depend on China.

You must be logged in to post a comment.