Executive Summary

- Insurance companies are reacting to the increase in climate change-related natural disasters by raising premiums and withdrawing coverage from high-risk areas.

- As extreme weather events grow in prevalence and unpredictability, insurance is becoming less accessible, mortgages are more difficult to secure, and housing is growing increasingly unaffordable.

- Governments may be forced to intervene with disaster-related insurance policies as the insurance crisis worsens and property values in high-risk areas plummet.

Introduction

As costly extreme weather events become more frequent, insurance companies are incorporating climate change concerns into their risk assessment process and adjusting their insurance policies to reflect the heightened threat of natural disasters. As a result, insurers are raising premiums and withdrawing coverage from areas at high risk of natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes.

Under the existing insurance framework, the growing economic burden of climate change is mostly falling on homeowners in disaster-prone regions. For these residents, insurance is becoming less accessible, mortgages are more difficult to secure, and housing is growing increasingly unaffordable. As the insurance crisis worsens and property values in high-risk areas plummet, governments may be forced to intervene with disaster-related insurance policies. This insight unpacks how climate change is shaping the U.S. housing market, and how reinsurers, insurers, and governments have been responding.

Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events

There is mounting evidence that extreme weather events will grow in severity and frequency due to climate change. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s historical records of billion-dollar weather and climate events reveal a prominent upward trend in the number of disaster occurrences exceeding $1 billion in damages from 1980 to 2024. Moreover, the cost of these disasters has also been rapidly increasing, depicted in the graph below. In the years prior to 2005, the inflation-adjusted cost of billion-dollar disasters in the U.S. rarely surpassed $50 billion and never exceeded $100 billion. In the most recent ten years, however, the average annual cost exceeded $140 billion.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Insurance Company Responses

Reinsurance companies such as Swiss Re and Munich Re were among the first to react to climate change threats since the 1970s. As insurers for insurance companies, it was crucial for reinsurance companies’ business models to reflect how climate change would impact risks to their portfolios. To that end, reinsurers pursued geoscientific research and developed natural catastrophes models to understand the financial impact of climate-related disasters.

Natural catastrophe models, such as the NatCat Modelling Engine developed by Swiss Re, are designed to leverage existing data and forecasting models to simulate stochastic events to predict the frequency and severity of potential hazards, assess a given portfolio’s vulnerability to damage, and quantify the potential financial consequences of natural disasters over long periods of time. The outputs from these models enable reinsurers to more accurately estimate the expected claims frequency and expenditure per claim, which are used to manage their policies accordingly.

Insurance companies have since followed the lead of reinsurers by integrating climate-related risk into their risk assessment processes. By incorporating climate change data and catastrophe modeling, insurers can better evaluate the threats to assets posed by natural disasters and determine sustainable policies accordingly. In practice, this information leads insurance companies to raise premiums and withdraw coverage from high-risk areas. While these measures help insurers stay financially sustainable, they shift the burden onto homeowners.

Climate Insurance Crisis

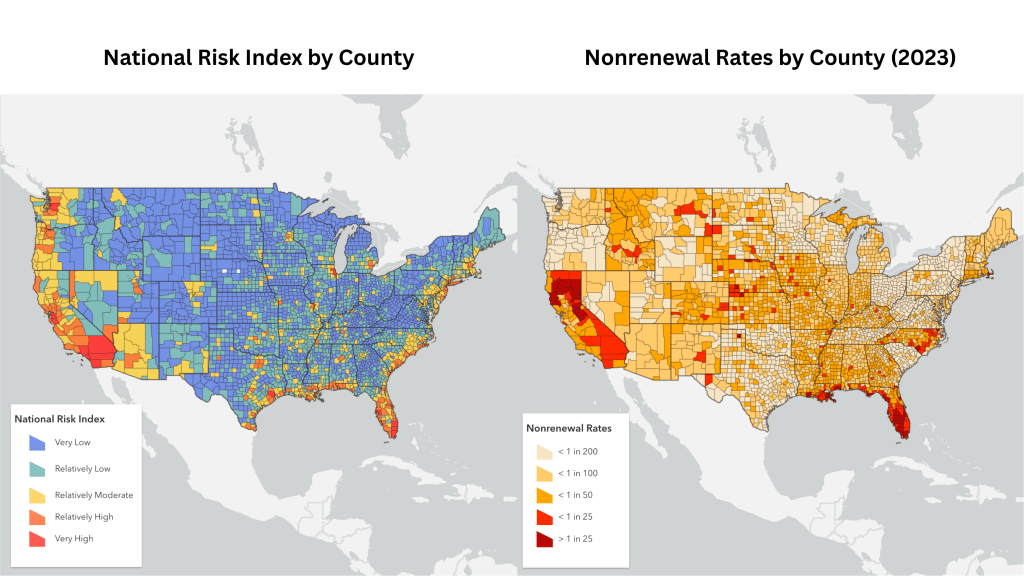

The insurance-related economic consequences of climate change are not distributed uniformly across the United States. An analysis of 23 insurance companies across the U.S. conducted by the Senate Budget Committee found that counties that are most exposed to climate-related risks are facing the highest non-renewal rates, the percentage of insurance policies not offered a renewal when the current policy ends. The following side-by-side U.S. maps visually confirm that the areas facing the highest risk of natural hazards—notably California and Florida—correspond to areas facing the highest non-renewal rates. The Federal Insurance Office of the U.S. Department of Treasury conducted a related study supporting these findings, reporting that people living in ZIP codes with the top 20 percent expected annual climate-related losses had 82 percent higher premiums ($2,321 higher) on average than those living in the lowest 20 percent of ZIP codes.

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), U.S. Senate Budget Committee

The insurance protection gap is the portion of disaster-related economic losses left uninsured. In 2024, the total economic disaster-related losses in the U.S. reached $199 billion but only $107 billion of those damages were covered by insurance, leaving a 46% protection gap. If insurance companies continue to withdraw coverage as the cost of natural catastrophes simultaneously treks upwards, this protection gap is poised to widen even further.

Source: Swiss Re

Responses from the Government

The Senate Budget Committee report on the climate-driven insurance crisis raises the possibility of the insurance protection gap cascading into a full-fledged financial crisis, if property insurance becomes inaccessible in high climate-risk areas and property values continue to plunge. This highlights the urgency of the issue and signals a pressing need for government intervention.

Funding Climate Research

In 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Science Foundation announced the joint creation of a research center to support the development of catastrophe modeling and climate risk assessment for the insurance industry, building upon previous efforts from reinsurers and insurers to adapt to increased extreme weather events.

While this initiative helps insurance companies refine risk assessment processes, improving insurers’ access to accurate information is only part of the solution. The primary beneficiary of this research center will be insurers, as they are able to set appropriate policies that better reflect climate risk that supports their long-term financial stability which often come at the expense of policyholders. Arguably, the more critical challenge for the government isn’t to help insurers react to climate change but to ensure that the housing market doesn’t collapse in high-risk areas. To do this, the government may have to step in to provide financial support to homeowners facing unaffordable premiums or non-renewal of their insurance policies, in the form of publicly funded climate risk insurance.

State Level Insurance Plans

State governments have been involved in insurance since the Urban Property Insurance Protection and Reinsurance Act of 1968. Today, nearly three dozen states offer Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans, which serve as last-resort property insurance plans to provide coverage for those who do not have access to insurance. FAIR plans, although typically more expensive and offer limited protection compared to privately managed insurance, ensure that owners of high-risk properties at least have some access to insurance coverage. If insurers continue to withdraw coverage from high-risk areas and more policyholders resort to FAIR plans, however, the financial stability of these plans may be at risk.

Federal Level Insurance Plans

The concept of federal insurance for natural disasters is also not new. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), administered by FEMA, has existed since 1968 in response to unaffordable or unavailable flood insurance in the private insurance market. As of February 2025, the NFIP provides $1.3 trillion in coverage to almost 4.7 million policyholders. This program, however, is expensive, costing American taxpayers over $40 billion. Moreover, the NFIP contributes to the national deficit, with $20.5 billion owed to the U.S. Treasury. In comparison, FEMA’s borrowing authority is limited to $30.425 billion, which raises concerns for the program’s long-term viability. Creating new or expanding existing insurance assistance programs like NFIP to cover additional extreme climate disasters would require additional federal spending and risks further increasing the federal deficit.

Promoting Climate Resilience

Publicly funded insurance programs, however, simply shifts the economic burden of increased natural disasters to public insurers and does not address the fundamental issues that are forcing private insurance markets to withdraw coverage or raise rates in the first place. Furthermore, keeping insurance affordable for homeowners in high-risk areas is only possible because residents of lower risk areas help subsidize rising insurance costs. Increased climate-related risks will raise prices for everyone in the insurance pool.

A proposal that tackles the root of the problem is for state and local governments to make targeted regulations that promote climate resilience measures and reduce vulnerability to hazards, while simultaneously incentivizing private insurance companies to continue offering coverage in high-risk areas. Investing in technologies that make properties more resilient to natural disasters could also lighten the economic burden for all involved parties. For example, Howden Re’s analysis reported that a $6 billion investment could halve the economic losses from Los Angeles wildfires, saving $38 billion. Updating building codes to improve infrastructure resilience in ways that reflect local disaster concerns could give private insurance companies the confidence to refrain from abandoning high-risk areas.

Looking Forward

Based on the current climate trend, an increase in climate-related disasters appears inevitable. This prompts the critical question of how this added financial burden will be distributed among insurers, homeowners, and the government. Navigating this uncertainty will not only require risk assessment processes that factor in climate change, but also thoughtful collaboration and innovative frameworks to address this increasingly prominent challenge.

You must be logged in to post a comment.