Note this post was written on June 17, 2025 and does not reflect subsequent events.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The pre-2012 consensus that increases in oil prices had a large negative effect on US output is no longer reliable. New evidence suggests oil price moves up to $115 per barrel will have an insignificant effect on total output due to the rise of US shale production.

- However, economic literature is still sparse in the post-2012 era. And the 2022 oil shock, triggered by the Russia-Ukraine war, failed to provoke a strong U.S. supply response, challenging earlier assumptions.

- Policymakers should be prepared for adverse impacts to the economy despite America’s current status as an oil exporter.

INTRODUCTION

High oil prices are top of mind these days for good reason. Brent oil prices have spiked more than 12% from $64 per barrel at the beginning of June to $72—mostly on fears of a Strait of Hormuz blockade. If Iran really does close the Strait, JP Morgan estimates oil prices could end up between $120 and $130 per barrel.

This analysis covers how the American economy would respond.

WHAT WE THINK HAS CHANGED

In the 1970s or even 2010, an impending oil shock would have been a five alarm fire. As James Hamilton explained in his 2009 congressional testimony:

“Big increases in the price of oil that were associated with events such as the 1973-74 embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, the Iranian Revolution in 1978, the Iran-Iraq War in 1980, and the First Persian Gulf War in 1990 were each followed by global economic recessions.”

And though there were other problems in the economy then, even the 2008 Great Recession had fingerprints of an oil shock. Gas prices spiked to $4 in June 2008 and tracing the ripple effects through to the recession is not hard.

Luckily, today the US economy at least appears more resilient to increases in oil prices. In the 2010s, US shale oil production boomed due to advances in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing; the US has gone from being the largest oil importer to being a net exporter. Naively, if you’re the one selling oil, price hikes should be good news.

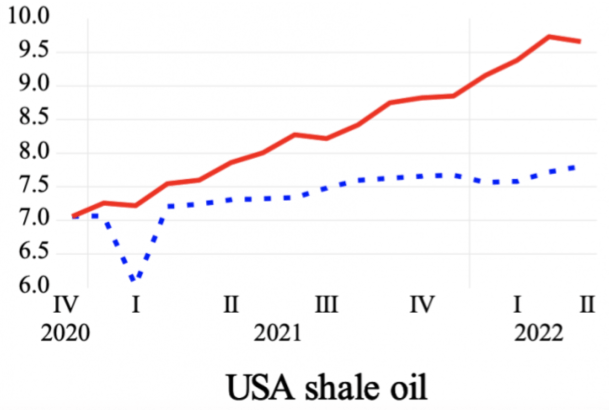

Potts and Yerger (2024) adds some economic precision. They use the Tsay test—a statistical model for identifying structural breaks in time series—to check for a shift in the relationship between oil prices and economic activity in the 2010s. And somewhat miraculously, the math matches common sense! The model spits out a breakpoint of September, 2012, which matches the eye test:

Potts and Yerger also show that what matters economically is not whether America is an importer or exporter of oil. Rather, what matters is whether higher oil prices stimulate enough additional activity in the oil industry to offset depressed activity elsewhere. The upshot is that until oil prices cross $115 per barrel, oil price increases will have negligible effects on the economy—so even the scenario of $130 per barrel wouldn’t be a disaster. Before that threshold, they predict US shale producers will be able to increase supply at low marginal cost. And generating that new supply means increased economic activity.

But just because the model lines up with intuition does not mean we should take the results at face value. Potts and Yerger (2024) is one study that is limited to data from before the pandemic.

WHAT WE KNOW WE DON’T KNOW

Unfortunately, there is a big reason to doubt Potts and Yerger’s story: American oil supply response in 2022. In 2022, with the Russo-Ukrainian War and resulting sanctions disrupting the market, oil prices shot up to $120 per barrel. Analysts expected US oil producers to jump into action. They didn’t:

There are many reasons floating around for why. Maybe the shock was too temporary; maybe rising interest rates made companies reluctant to invest; maybe the government was too slow in giving permits. But this was a real live oil shock, and the theory didn’t pan out.

Then, there’s the market. The market is currently sounding optimistic notes. When Israel’s attacks first kicked off, US treasury yields went up. This implies the market thinks an oil shock will cause the Fed to tighten rates; the market is more worried about higher inflation than higher unemployment and recession. More importantly, stocks have hardly reacted even as betting markets on a potential blockade have swung widely. This indicates markets either aren’t that stressed about the worst case scenario or they don’t think a blockade will blot corporations’ bottom lines.

CONCLUSION

In sum, there’s nothing to hang your hat on; policymakers should be ready for substantial economic uncertainty if oil prices spike. All we do know is that if enough bombs fall in the Middle East, economists will learn more about post-2012 oil shocks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.