Executive Summary:

- In response to the Chinese government’s threated export controls on rare earth minerals, the Trump administration has signed frameworks for cooperation on rare earth mining and processing with several countries.

- Almost all of these frameworks specifically mention price floors and other pricing controls as a potential policy tool.

- Though China is certainly engaging in market manipulation through providing large subsidies to its state-run companies, price controls may result in more market distortion than other policies.

Introduction

On October 9th, China imposed export controls on rare earth minerals and related technologies. Since then, rare earth minerals have been dominating news headlines, with many experts espousing the importance of reducing the U.S.’s dependence on China for these minerals. The Trump administration’s policies have heavily focused on rare earth minerals too; the administration signed individual frameworks for cooperation on rare earth mineral mining and processing with Australia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Japan just within the past few weeks.

Though China paused its newest export controls following bilateral talks between Xi and Trump, the threat of future export controls still looms on the horizon. The U.S. is also certainly aware of this threat, as demonstrated by the myriad of bilateral deals focused on shifting critical mineral supply chains away from China. Interestingly, each of these bilateral deals mentions price mechanisms, and some even mention price floors, as a potential policy tool for developing alternative supply chains.

What are rare earth minerals?

Rare earth minerals (REESs) are minerals containing combinations of 17 metallic elements with similar physical and chemical properties. These elements include the 15 lanthanides, as well as scandium and yttrium, which have similar properties. There are also “heavy” and “light” rare earth elements, which are classified depending on their atomic number. Light rare earth elements tend to be more abundant and easier to extract and are often used for magnets and wind turbines. On the other hand, heavy rare earth elements are used for many high-tech innovations, including advanced sensors and lasers.

Why were China’s threatened export controls so worrisome?

Though rare earth minerals are not actually rare, what makes them important is their use in technological products, for everything from EVs to the defense industry. As the world’s largest supplier of rare earth minerals, China mines 70% of the world’s supply and processes around 90%. China’s threatened export controls, which required firms to apply for a license to export magnets, semiconductor materials, and other tech products that contain at least 0.1% rare earth elements, could thus cripple the defense and technology sectors of the U.S. and other Western powers. With China’s Ministry of Commerce stating that licenses for military usage would not be approved, the U.S. defense industry clearly stands in an even more precarious position.

The Argument for Price Controls

Given the national security risks of remaining dependent on China for rare earth minerals, the U.S. must do something to develop an alternative supply chain. Price controls have been proposed as a potential policy tool in the development of such a chain.

The argument for price controls rests primarily on the premise that China “flooded [global markets] with excess supply to push prices so low that mines in countries like the United States and Australia become unviable.” From a historical perspective, this seems plausible. During the 1970s, the U.S. Mountain Pass mine produced approximately 70 percent of the world’s rare earth supplies, providing for 100 percent of U.S. demand. As NPR reports, after seeing the success of rare earth mines in the U.S., Chinese companies began opening refineries. Lower labor and electricity costs made mining extremely profitable in China, with many private mines and refineries joining the industry. But the lack of regulation and the large number of firms entering the market led to fierce competition between firms, driving down prices. Moreover, in 2011, the Chinese government forced its rare earth companies to consolidate into the Big Six, six incredibly large, primarily state-owned firms. This allowed the Chinese government to control the supply and price of rare earth minerals. In 2021, the China Rare Earth Group was established, merging Chinalco, Minmetals, and Ganzhou Rare Earth Group, three of the Big Six companies. This furthered the Chinese Government’s control over the rare earth industry.

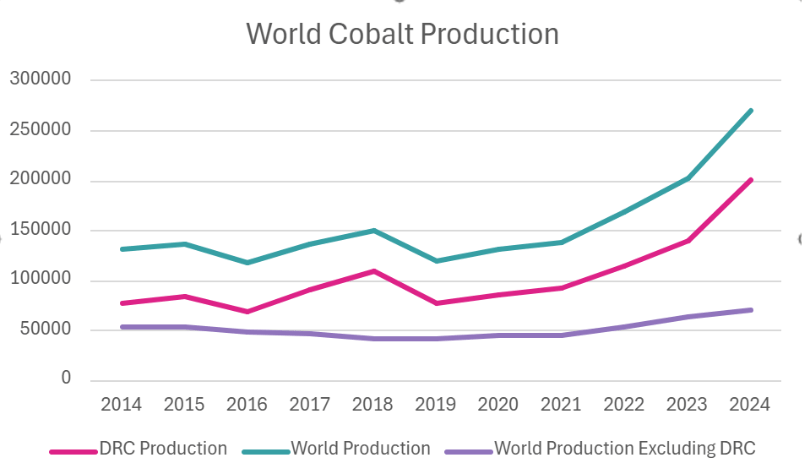

In recent times, experts argue that competition amongst Chinese firms is no longer the primary force driving down prices; instead, China seems to be specifically controlling the prices of rare earth minerals through these state-owned firms with the goal of preventing alternative supply chains for developing. For example, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) proposed that the Chinese government’s market manipulation is evident through cobalt prices, which fell 59.5 percent between May 2022 and May 2025. CSIS ties this to Jervois’s new U.S. cobalt mine, which closed the same year it opened due to low cobalt prices. CSIS also points to nickel prices as evidence, which fell 73.1 percent from March 2022 to May 2025, forcing BHP to close its mines in Australia and Glencore to close its mine in New Caledonia. If this evidence is accurate and Chinese companies, along with the Chinese government, are truly engaging in market manipulation, the argument can be made to respond with price controls.

Does China Actually Engage in Unfair Pricing Practices?

In the context of international trade, unfair pricing practices are often described in terms of dumping and countervailing subsidies. In this case, both practices can apply. Dumping typically includes companies selling below the cost of production, but also often includes predatory pricing. As a part of predatory pricing, firms will price their products below the domestic prices of a competitor firm, thus pushing out domestic firms and gaining market share. This can allow the firm to gain a monopoly over the market, and then to raise prices, harming consumers and downstream producers. On the other hand, countervailing subsidies occur when foreign governments provide financial aid to specific industries.

To see the case for price dumping, one can focus on the example of cobalt presented earlier. Jervois stated that it needed cobalt prices of at least $20 per pound to keep the mine open. In 2021, when Jervois received approval for finalizing the construction of the plant, Cobalt spot prices sat above $23 dollars. When commercial production began in 2022, cobalt prices still sat consistently above $20 dollars. However, in 2023, cobalt prices dropped below $20 to around $15. Jervois suspended production of cobalt that March, citing low prices.

If China engaged in market manipulation and dumped cobalt to prevent Jervois from developing as an alternative cobalt supplier to the U.S., one should be able to see a clear increase in Cobalt production specifically by Chinese companies despite falling prices prior to the mine’s closure in March. But the data does not support this argument. First and foremost, prior to 2023, Glencore, a U.K-Swiss based mining company, was the largest producer of cobalt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where 73% of the world’s cobalt supply was mined. The CMOC Group, a Chinese mining company, opened its Kisanfu mine in 2023, surpassing Glencore as the largest producer of cobalt that year and driving cobalt prices lower as supply continued to outpace demand. However, cobalt prices had already been declining since before May of 2022 –thus the CMOC Group clearly cannot be to blame. Moreover, CMOC had a difficult year throughout 2022, as the Tenke Fungurume Mine faced an export ban until April 2023. So while CMOC did increase production throughout 2023, the fact that Jervois had already closed its mine in March highlights the fact that in this case, Chinese dumping may not be to blame.

Examining the overall cobalt price over a 10-year period and production of cobalt further highlights this discrepancy. Chinese firms primarily mine cobalt in the DRC. Although cobalt production in the DRC increased in 2023, the rate of increase seems consistent with the overall rate since 2019, far before Jervois even opened their mine. Moreover, cobalt prices, as reflected in figure 3, are rather inconsistent. The 59.5 percent price decrease in cobalt prices from 2022 to 2025 – cited by CSIS as evidence of dumping –was calculated by examining cobalt prices at their peak in 2022, before they fell back down again. So, at least in this case, it doesn’t seem that China purposefully flooded the cobalt market to decrease prices and force Jervois out.

This, of course, does not rule out the possibility that China is providing countervailable subsides to its companies, thus giving them an unfair advantage in critical mineral production. In fact, evidence of such subsidies is quite clear. For example, China Northern Rare Earth Group High-Tech Co. received $21 million in government subsidies in 2020. Moreover, half of China’s provincial governments provide subsides for mineral exploration, and from 2001 to 2009, its estimated rare-earth state-owned enterprises in China can attribute all their profits to state subsidies. This is on top of the tax breaks, land subsidies, and low interest rates specifically given to rare earth companies. So, while China may not have been culpable in the cobalt-case, they are certainly guilty of unfair market practices that have allowed their companies to continue operating.

Will price controls actually help?

It is clear China is engaging in unfair market practices. While claims of dumping may not be fully accurate, it is evident that China is subsidizing Chinese rare earth mineral companies, thus influencing market dynamics.

To both protect its national security and combat unfair trade practices, the U.S. should address the issue of unfair market practices. Price floors are one answer to this problem and seem to have already been selected as the solution. Price floors have been used for national security relevant industries in the past; during WWII, while facing a copper shortage, the U.S. established a “premium price” of 17 cents per pound to increase the production of copper, and the subsidy did seem to be successful. But price floors also have well-known limitations, and CEOs of mining companies have already spoken out with concerns. Price floors in general already have many risks; they often distort market signals and can decrease incentives for innovation, which is crucial if U.S. firms are expected to catch up to Chinese mining technology while also seeking to reduce harmful environmental impacts.

Other policy tools may distort the market less and prove more effective. For example, coordinating with allies to impose countervailing duties on Chinese rare earths and related technologies will protect domestic producers while still preserving incentives for innovation and other market signals. Even more effective policy tools include decreasing the administrative burdens and environmental compliance measures imposed on rare earth companies.

In the end, incentivizing domestic rare earth mineral companies and production will certainly require policy tools to combat China’s market manipulation. But rather than relying on tools such as price floors, the U.S. should consider a myriad of possible solutions while seeking to prioritize innovation and investment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.