Executive Summary

- Electricity is a necessary commodity for nearly every person in the United States, and while the delivery process has not changed, deregulation has altered who supplies it.

- Historically, electrical markets were vertically integrated and regarded as a natural monopoly, but recent market-oriented reforms have aimed to deregulate and introduce competition to lower both wholesale and retail prices.

- This analysis uses a difference in difference (DiD) approach to study the effects of retail electricity deregulation on prices in Illinois (a fully deregulated state) and Indiana (a partially deregulated state), finding that while prices rose overall, prices in Illinois increased at a slower rate than Indiana.

Introduction

Electricity has become the most fundamental commodity in the United States. Its growing influence underpins nearly every major industry. It powers homes, infrastructure, and manufacturing. Innovation and technological development for the entire economy depends on efficient and reliable energy transmission.

Utilities markets in the U.S. have historically been viewed as natural monopolies. A natural monopoly is defined as when a market is provided for most efficiently by a single firm. Because of this assumption, electricity markets were formed to be vertically integrated. Utility markets were initially vertically integrated and thought of as natural monopolies because of geographic necessity and structural simplicity. Technological limitations in efficiency and large capital and infrastructure requirements also supported vertically integrated monopolies. In this structure, one company owns the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity. In the United States, vertically integrated electricity firms are regulated by governing agencies in the form of rate setting and expansion approval. Regulators believed this structure created efficient and reliable outcomes for consumers.

In recent decades, economic perspectives have shifted to support a market-oriented structure. In some states, the process is divided into multiple wholesale and retail firms, with the goal that the introduction of competition will decrease prices for both wholesale and retail firms. Electrical markets can be deregulated in many ways. Certain states have chosen to only deregulate the wholesale market while keeping a single retail provider as the sole suppliers to consumers, like in Indiana. Bidding in the wholesale market fosters competition to create better outcomes for consumers. Other states have chosen to fully deregulate their markets, like in Illinois, with both wholesale and retail firms having to compete for customers. Full deregulation gives consumers the choice of energy provider.

Illinois implemented the Electric Service Customer Choice and Rate Relief Law which fully deregulated its electrical market. This law was passed in 1997, with a phase-in period that provided full consumer retail choice by 2002. Before this, Illinois residents saw some of the highest electricity prices in the country. Illinois used a cost-of-service regulation model, where firms recoup their costs plus a reasonable profit margin. The cost-of-service regulation model used in Illinois did not promote innovation, technological advancements, or price reduction. The restructuring of the wholesale and retail market by ending the cost-of-service model allowed consumers to choose their providers with the hopes of lowering retail prices.

This study employs a Difference-in-Difference (DiD) approach to examine the impact of retail electricity deregulation in Illinois compared to Indiana. Illinois has a fully deregulated market, while Indiana has only deregulated its wholesale market. This isolates the effects of retail deregulation. This study seeks to examine whether the shift towards a market-competitive structure lowered the price of retail energy in Illinois. These findings contribute to the broader understanding of deregulation’s impact on consumer prices and market efficiency.

Theory and Literature Review

Theory of Monopoly, Markets, and Competition

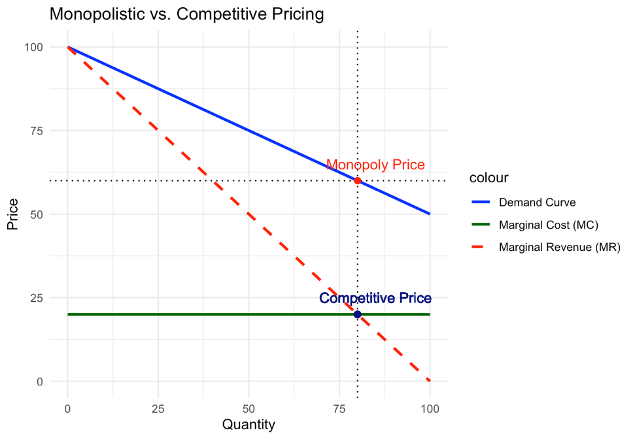

In economic theory, monopolies price off their marginal cost curve. In a competitive market, the marginal cost is equal to the marginal revenue. The marginal cost curve shows how the cost of production changes as the quantity of products increases. Monopolies set a price above the marginal cost, restricting output while maximizing profits by charging a higher price. Setting prices in this way introduces allocative inefficiency and is not representative of the true cost of the product. With no regulation, monopolies force consumers to pay more than the efficient price because of market power.

Regulations, like the one in Illinois prior to 1997, introduce price caps that limit the price a firm can charge to control for monopolistic pricing patterns. While in theory this tactic works, in practice, it is not as effective. Regulations structured in this way are prone to not capture the actual price of production and become outdated or inflexible. This means electrical firms cannot accurately respond to underlying changes in producer prices. Since the value of the true cost of electricity is not presented, inefficiencies from deadweight loss are introduced into the market. These inefficiencies are costly to both producers and consumers in the form of higher prices.

Given these challenges, some policymakers argue that fostering competition can better align prices with production costs. Competitive markets seek to correct the problems of monopolistic pricing and price-cap regulations. In a competitive pricing model, firms compete against each other. Competition lowers the price to consumers towards the true cost of production. A distinct feature of this model of markets is the consumers’ access to information and the ability to compare prices across firms. A market-oriented structure also incentivizes efficiency and innovation. In this model first must reduce costs and adopt new technologies to gain a competitive edge in the market. When customers can compare prices, firms are now pressured to offer more competitive rates which increases quality and lowers prices.

Literature Review

Deregulation is an umbrella term that constitutes many different mechanisms. The specific mechanism of deregulation this study seeks to explore is retail customer choice in electrical providers. The literature on vertically integrated utilities trends in favor of suggesting competitive market alternatives, while the literature on the effects of utilities deregulation offers a mixed consensus.

In the article “Electricity networks: how ‘natural’ is the monopoly?” Künneke argues that technological advancements have put a strain on the historical perspective that electrical firms are natural monopolies. He finds that the EU has seen increases in efficiency, like power output and load management technologies, which have decreased the barriers to entry in the electrical market. High fixed costs associated with entry, along with economies of scale, are traditionally what kept many firms from entering the electrical market. With these advancements Künneke challenges the traditional view on vertical integration and natural monopolies. Künneke’s work focuses on efficiency in electrical generation and does not address changing market dynamics in the United States. While offering valuable insight supporting market alternatives to vertical integration, his analysis is focused on the European Union, which has differing electrical markets and regulatory structures. Künneke’s work underscores how the declining technological barriers weaken the justification for vertical integration.

Joskow’s article “Lessons Learned from Electricity Market Liberalization,” provides a qualitative analysis of the effects of liberalized electricity markets across the globe. His research suggests the success of a competitive market model depends heavily on the structure of the changing regulations. Joskow places emphasis on the structure of deregulation, and policies should promote competition rather than completely deregulate a market. In countries where regulation changes did not promote robust competition, market power was consolidated which effectively dismantles the premise of deregulation and consumer choice. Joskow also illustrates that the percentage of customers switching to competitive retail suppliers in Texas increased from 10 percent to 60 percent in the span of only four years. This rapid adoption in Texas suggests that when consumer choice is properly facilitated it can drive market engagement. He concludes his paper by emphasizing under the right regulatory conditions, deregulation improves efficiency gains without any reduction in the quality of service. This provides an important analysis into understanding the importance of the regulatory environment in fostering competition. While Joskow’s insights into regulatory structure are valuable, his study would benefit from econometric analyses to determine efficiency gains/losses. This paper seeks to expand further than efficiency gains and determine the impact on retail prices.

A working paper by MacKay and Mercadal titled “Do Markets Reduce Prices? Evidence from the U.S. Electricity Sector”suggests that the electricity sector does not benefit from the establishment of market-based incentives. Their paper emphasizes the broader concerns of rising prices and the consolidation of market power stemming from deregulation. This study finds similar increases in efficiency and lower generation costs as found in Joskow and Künneke, but also an increase in wholesale electricity prices. The authors also raise valid concerns about the effects of contracts and firm divestiture on market power. MacKay and Mercadal’s primary question is the effect on wholesale prices, while the current study examines retail prices. This study also focuses on an inter-state comparison, rather than using wholly regulated states against wholly deregulated states. The current study’s comparison also focuses on the effect of retail deregulation, as the control state of Indiana also has a deregulated wholesale market. While offering strong empirical evidence, this paper takes a step further in understanding the additional impact of retail deregulation over wholesale deregulation.

Existing literature largely supports responsible deregulation of electricity markets and emphasizes the importance of deregulating in a manner that promotes competition. A strong increase in electrical generation and storing technologies has removed barriers to entry, challenging the efficiency of vertically integrated utilities. Market-based principles have led to efficiency gains in electricity markets in the form of generation cost. While prior studies highlight efficiency gains in generation and wholesale pricing, the impact of retail competition on consumer prices is understudied. This paper aims to fill the gap and examine how deregulation effects retail prices.

Methodology

Data

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) provides data on retail sales and revenue for all end use sectors from form EIA-861M. This dataset spans from 1990 to 2024 in monthly increments for Illinois and Indiana. It provides revenue, sales, and number of customers, as well as prices for residential, commercial, industrial, transportation, and total categories. For this analysis total price, which is a weighted average, is used to determine the effect on all end use customers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides employment data by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code. NAICS22 is used as it encompasses the utilities industry. The number of firms and employees inside the states included in the analysis are extracted from the dataset. The dataset spans yearly from 1978 to 2022. The number of firms and employees is used to control for each state’s industry size. State population data is sourced from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). Population data is taken yearly and measured in thousands. The aggregated dataset contains annual observations spanning 33 years, from 1990 to 2022.

Because of the volatility of electricity prices, the log is taken to reduce skewness and improve normality in the dataset. This is also done to determine the percent change effect on prices, rather than absolute magnitude. This is beneficial for interpretability and comparison across studies.

The states included in this study are Illinois and Indiana. Illinois and Indiana mostly receive their energy generation from the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO). This provides additional comparability. These states are also situated geographically adjacent and have similar economic structures. Both states also have a deregulated wholesale electricity market, which allows this study to isolate the effect of retail deregulation.

The Electric Service Customer Choice and Rate Relief Law allowed for full retail customer choice in 2002. As standard in a DiD model, a dummy variable is created where every observation post 2002 on is equal to one. A treatment dummy variable is applied to the state of Illinois, where the law was passed. The treatment variable is equal to one in Illinois and 0 in Indiana. An interaction dummy variable is created and equal to one if post 2002 and treatment are both equal to one. A placebo interaction term has also been applied at 1995 to ensure robust results.

Difference-in-Difference Model

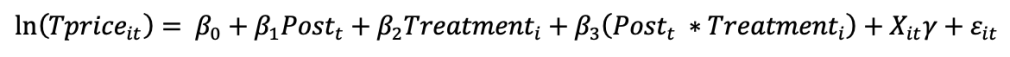

The below DiD equation is used to estimate deregulations effect on prices.

Where:

- ln(Tpriceit) is the log of retail electricity price at time t and state i

- Postt is the period after 2002

- Treatmenti is a dummy variable for Illinois

- (Postt * Treatmenti) is the interaction term capturing deregulation’s effect

- Xit represents control variables population, number of firms, and number of employees

- eit is the error term

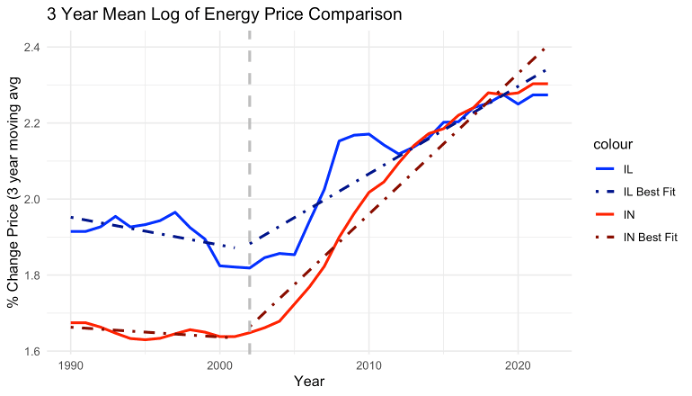

This study uses a DiD model to estimate the impact of retail electricity deregulation on prices. DiD is a useful econometric method for evaluating the effect of policy implementation. A DiD model mimics a natural experiment that compares trends in a treatment group (Illinois with complete deregulation) and control group (Indiana with partial deregulation) over time. This method works by isolating the time frame where deregulation occurred, in this case 2002, and having that period interact with the treatment group. This method helps isolate the causal effect of retail deregulation by controlling for shared economic trends in both states. Using a DiD model relies on the assumption there are parallel trends in prices in the absence of regulation. To test for parallel trends, the dummy variable is included at 1995 and a visual inspection of price trends before 2002 can be seen in the table below. The figure below shows the three-year moving average of the log of electricity prices for Illinois and Indiana. Before 2002, the best-fit trend lines show similar movement, which supports the parallel trends assumption.

Results and Discussion

Empirical Results

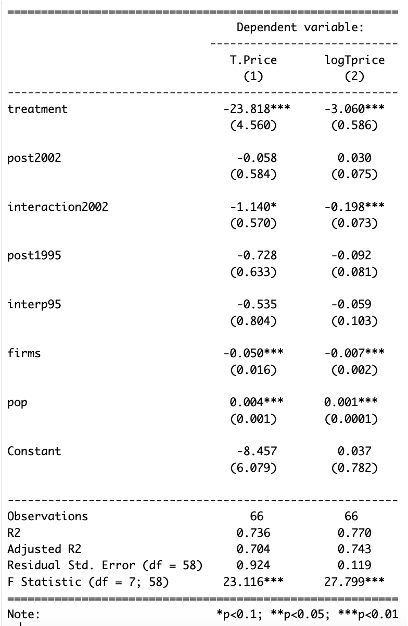

The adjusted R-squared of second model is 0.743, suggesting that 74.3 percent of the variation in the log of price is explained by the model.

The coefficient on population is positive and statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level. Based on the model, an increase in one unit of population is predicted to increase the retail price by approximately 0.1 percent, holding all else constant.

The coefficient on firms is negative and statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level. This relationship suggests that increasing the number of firms by one unit is predicted to decrease the price of retail electricity by approximately 0.7 percent, holding all else constant.

The regression results table includes both the raw price and the log-transformed price. The coefficient on the treatment for the log price is -3.060 predicting that the average price in the treatment group, Illinois, is lower than in Indiana, holding all else constant. This coefficient is statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level.

The coefficient on post2002 is positive and not statistically significant. This suggests there is no statistically significant difference in prices pre and post 2002 when controlling for other variables.

The interaction term, the key component of the DiD model, is negative and statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level. The coefficient suggests that in Illinois in the post period when compared to Indiana, the price is predicted to decrease by approximately 19.8 percent, holding all else constant.

A placebo variable is also added at 1995 to ensure robust results and satisfy the parallel trends assumption. The parallel trends assumption is integral to the DiD design. It assumes that without the policy enaction, prices move in tandem in both locations. By adding another interaction term in 1995, this tests whether there is a divergence in prices before the policy was implemented. The coefficient for interp95 is not statistically significant, which suggests the parallel trends assumption holds based on this model’s specification.

Discussion

Electricity markets are complex because of the ever-changing regulatory landscape, technological advancements in energy, and the volatile supply of energy. Even still, electricity is an inelastic good where price changes do not have a large impact on consumption. Because of its inelastic nature, consumer choice and reliable substitutes are essential for an efficient electrical market. Currently, 13 states have implemented retail consumer choice in electrical providers. Deregulation efforts in Illinois have created these substitutes to create efficiency gains and lower prices.

Retail electricity prices increased in all states in 2004. This could be from the 2004 oil crisis, which led to a sustained increase in the supply of energy. Because of this factor, this study examines the difference in price changes between the two states rather than a price increase or decrease. The explanatory power of the regression is further improved because Illinois and Indiana exist largely on the same ISO. This factor isolates the effect of retail deregulation and controls for broader economic conditions. The regression results indicate that deregulation efforts in Illinois were associated with a relatively slower rate of price increases compared to Indiana. Competition among firms for retail customers played a key role in slowing the rate of price increases. These findings align with Künneke and Joskow’s findings, which highlight that efficiency gains are associated with competitive retail electricity markets.

According to a study by the EIA, residential retail choice in Illinois has risen from 21 percent in 2015 to 26 percent in 2021. This shows a promising trend as more people are aware of price variations among suppliers and take an active part in deciding their electricity supplier. It also aligns with the findings in Texas presented by Joskow. The changing landscape in the electrical market is lending itself towards more pro-competitive structures. Vertical integration is becoming less popular and competition-based markets have comparatively slowed the rate of price increases for retail electricity consumers regardless of whether customers stayed with their previous provider or changed providers.

These results have important policy implications. Deregulation in Illinois ended the cost-of-service regulation model and allowed for consumer choice in their provider. The implementation of deregulation practices determines their overall success. Deregulation needs to be structured in a way that supports competitive practices and discourages aggregation of market power. MacKay and Mercadal raise concerns in the wholesale market that divesture led to contracts being owned by main players. To combat this, Illinois has instituted several commissions, projects, and legislative efforts to improve protections for consumers. The Illinois Competitive Energy Association, PlugIn Illinois, and Alternative Retail Electricity Supplier (ARES) regulations all help inform and protect consumers. These initiatives support deregulation as the dynamics of electrical technology policy changes favor a free market orientation. Policy should be focused on facilitating entry into the market while limiting consolidation by major players. The introduction of retail consumer choice, with strong protections, will effectively keep prices competitive.

Due to limited number of states having retail deregulation, its effect on consumer prices has not been extensively studied. As such, more research needs to be done to examine this policy in other states. Future research should examine the extent to which changes in wholesale electricity prices affect retail prices following deregulation.

Conclusion

This study employs a DiD approach to compare the retail electricity prices in Illinois and Indiana. Retail deregulation is isolated because both states have a deregulated wholesale electrical market. Evidence suggests that consumer retail choice has led prices in Illinois to increase at a slower rate than in Indiana. Although energy supply shocks have driven price increases overall, the transition to a pro-competitive market structure In Illinois has mitigated these effects. For states considering deregulation, ensuring consumer protections while fostering a competitive market is paramount to achieving sustainable benefits.

You must be logged in to post a comment.