Executive Summary

- Last month Canada and China reached a deal to reduce Canadian tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles in return for lower Chinese tariffs on Canadian canola products; this agreement reflects the pragmatic pivot North America has taken toward the Chinese agricultural market.

- The Trump Administration’s threat of 100 percent retaliatory tariffs on Canadian imports if a deal goes through has created unnecessary conflict with Ottawa.

- U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) Agreement partners must realize their shared interests in dealing with Beijing and, in one form or another, coordinate negotiations of such deals.

Introduction

On January 1st, 2026, a new set of Mexican tariffs came into effect amid pressure from Washington to curb trade with China. The increases in rates range from 5 percent to 50 percent on imports from non-free trade agreement partners, with some of the highest duties (50 percent) targeting electric vehicles (EVs). For the Trump Administration, it was welcome news, as it has expressed concern over China using Mexico as a backdoor for North American markets.

In the aftermath, observers have characterized the Mexican policy as a step toward North American trade policy synchronization in the lead-up to the USMCA review on July 1st. Yet, as Mexico harmonizes with American trade policy toward China, Canada is seemingly striking a different tone with Beijing.

Two weeks after Mexico City’s new tariffs came into effect, Prime Minister Mark Carney confirmed a deal with China that allows 49,000 Chinese EVs into the Canadian market at the preferential tariff rate of 6.1 percent; that 49,000 is allotted to grow to 70,000 Chinese EVs annually in five years. In exchange, China will lower its retaliatory duties on Canadian canola seed to 15 percent from 85 percent, Canadian canola meal to 0 percent from 100 percent, and begin investing in the Canadian auto sector by 2029. As the United States indulges protectionism, Ottawa has touted the arrangement as a victory for trade diversification.

President Trump’s ensuing threats to apply a 100 percent tariff on Canadian imports if a trade deal moves forward contribute to its interpretation as a rebuke of Washington. No formal duty has been filed yet, but lost in the back-and-forth, the agreement underscores a common North American interest in accessing the Chinese agricultural market. It was not two months earlier that the Trump Administration had penned its own deal with China to undo punitive duties on U.S. agricultural exports, mainly soybeans. As the USMCA states grapple with Chinese trade, they must work with these shared interests and coordinate, rather than penalize, their execution.

History of Canadian Canola and U.S. Soybean Exports to China

For both the United States and Canada, China is an integral export market for some of their most valuable agricultural sectors: canola for Canada and soybeans for the United States. These sectors have a large presence in the Chinese market, with billions to lose in the event of a trade conflict.

Canadian Canola

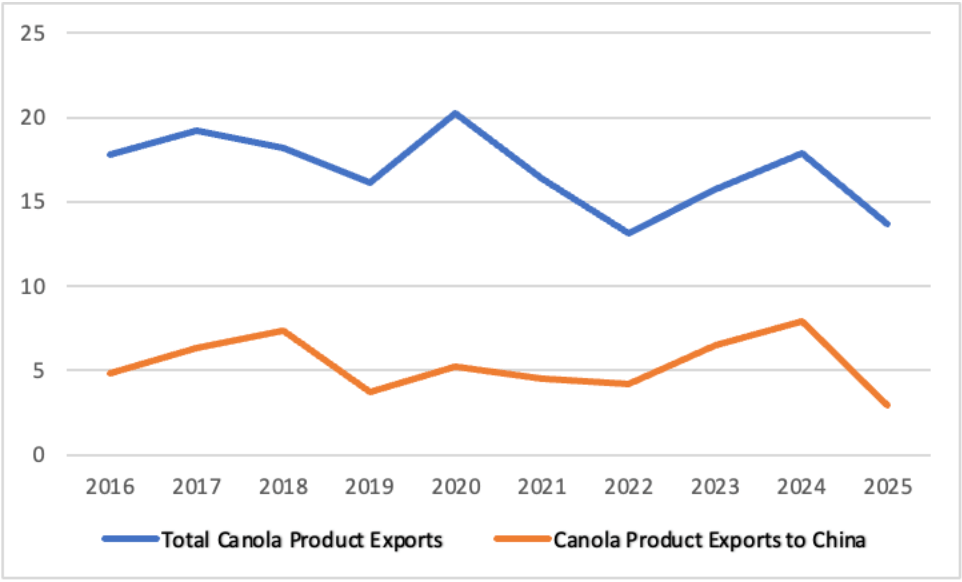

China opened its oilseed markets to outside supply in 1994, which triggered the rise of Canadian canola exports. According to the Canola Council of Canada, 90 percent of the canola produced in Canada is consumed abroad, and 44 percent of canola product exports in 2024 went to China. This represented $3.6 billion relative to the $32 billion in canola-derived Canadian economic activity that year.

The January 2026 deal has its origins in 2025, when Beijing imposed a 100 percent tariff on Canadian canola oil and meal, along with a 76 percent tariff on canola seed. This came after Ottawa levied a 100 percent antidumping duty on Chinese EVs. For its part, China heavily relies on Canadian canola imports. Using 2018 as a benchmark, 93.57 percent of canola seed imports, 98.12 percent of canola meal imports, and 84.72 percent of canola oil imports to China came from Canada. Annually, the share of total Chinese canola product imports from Canada hovers around 90 percent. Between March 2025 (the month canola tariffs were imposed) and September 2025, Canadian canola farmers lost an estimated $590 million due to depressed Chinese demand.

Figure 1: Canadian Canola Product Exports (MMTs) Total, to China (2016-October 2025)

Source: Canola Council of Canada

U.S. Soybeans

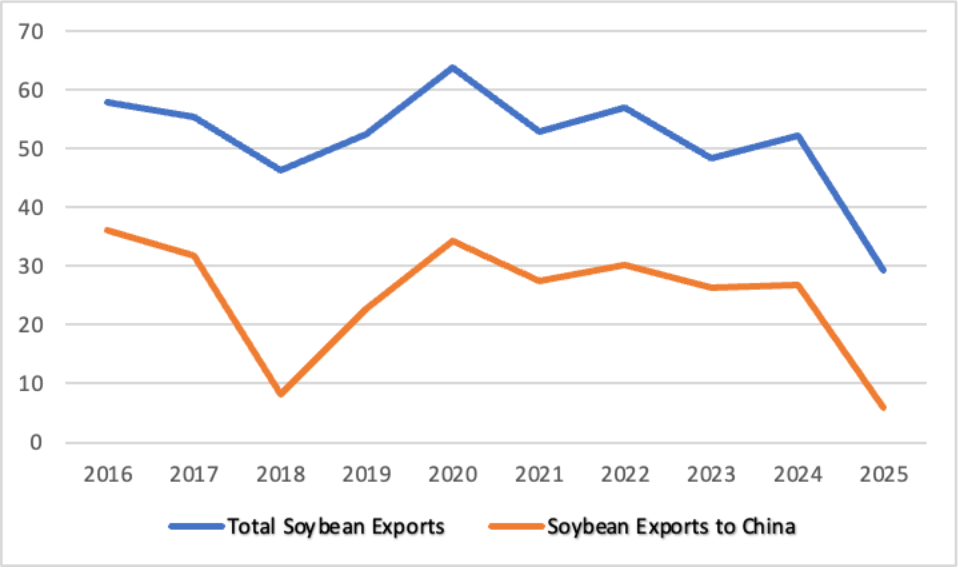

U.S. soybean exports to China similarly began to rise in the early 1990s, with China being the world’s largest soybean market. Accordingly, by the 2010s, the United States was consistently ranked as a top supplier of imported soybeans to China. U.S. farmers came to rely on the market, with an average of 50.2 percent of U.S. soybean exports going to China between 2015 and 2024. In 2024, that translated to around $12.6 billion.

Since 2018, soybean farmers have been a target of retaliatory Chinese actions in trade wars with the United States. In President Trump’s first term, on top of already in-place duties, China imposed a 25 percent retaliatory tariff on U.S. soybean imports, resulting in an estimated $9.4 billion in annualized losses for soybean growers in 2018-2020. Predictably, Trump’s renewed trade conflict with Beijing delivered another hard year for the industry in 2025. In combination with rising labor and input costs, U.S. soybean growers faced more retaliatory duties from Beijing, leading to an estimated loss of $5.7 billion in missed Chinese sales from April to October 2025.

Recognizing this dire situation, Washington finalized a deal with Beijing in November 2025, under which China agreed to purchase 12 million metric tonnes (MMT) of soybeans from November to December 2025, and 25 MMT annually for the next three years. This, along with other Chinese concessions, was matched by U.S. commitments to lower the cumulative tariff rate on Chinese imports by 10 percent and to postpone other punitive duties for a year.

Figure 2: American Soybean Exports Total (MMTs), to China (2016-2025)

Source: USDA FAS

A Mismanaged Response

Given the Trump Administration’s recent deal with Beijing, its initial response to the Canadian deal—passing approval—seemed warranted. When first questioned about the deal, President Trump regarded it as a “‘good thing‘” that Ottawa should be pursuing.

Only days later, the tone shifted. President Trump was now threatening 100 percent tariffs on Canadian imports if any deal with China proceeded. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent stressed the threat of Canada becoming a backdoor for dumped Chinese imports. Such American backtracking, incognizant of Washington’s own treatment of China, forfeits a potential point for USMCA cooperation.

Notably, the proposed tariff rate quota (TRQ) on Chinese EVs does not indicate a seismic shift in Canadian trade policy toward Beijing. The quota amount accounts for only 3 percent of the vehicles sold annually in the country, while the previously instated 100 percent tariff on Chinese EVs applies after the TRQ is met. 25 percent tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum imports remain in place. Still, those 49,000 Chinese EVs are unlikely to hugely hurt USMCA automobile producers when Chinese brands lack a network of car dealerships in the market. Ultimately, it is probable that the 10 percent rate reduction and other actions outlined in the U.S. deal will impact producers more than Ottawa’s TRQ.

USMCA Implications

Even so, the essence of both deals is identical: securing access to Chinese agricultural markets for China-dependent sectors while slightly softening trade controls on Beijing. This is a tough line to walk, but members should not allow it to destabilize the USMCA when their aims are aligned.

Instead of antagonizing Ottawa’s pursuit of its agenda, and with this recent spat weighing on the upcoming USMCA review, the North American partners could add an agricultural export promotion chapter into the revised agreement. At a minimum, the states can keep each other informed on their negotiations with China regarding such dealings. All three states recognize the security and economic threats of unchecked Chinese-North American commerce, and to avoid disputes such as the one above, measures from negotiating transparency to an export promotion scheme among commercial partners are suitable. The July 1st review provides an opportunity to adapt to this increasingly clear reality.

Conclusion

Mexican tariffs on non-FTA imports and the Canadian deal with China to expand canola exports are two sides of the same policy alignment coin. Just as North America needs to ensure that cheap, unfairly supported Chinese goods do not flood its market, China’s importance as an export market is a fact of the commercial landscape. If the Trump Administration hopes to create a North American tariff wall to fulfill the former, it needs to acknowledge that its goals in export preservation hinge on the latter. A strong USMCA zone will have to have a trading relationship with China: what shape that takes, and if its gains can be maximized, depends on coordinated trade policy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.