Executive Summary

- The relationship between fiscal deficits and trade balance in the United States is complex, and the twin deficit hypothesis (TDH) and Ricardian equivalence hypothesis (REH) suggests two differing opinions on the relationship.

- The TDH postulates a positive connection between fiscal deficits and trade balance (net exports) while the REH argues there is no distinct relationship between the two.

- While the results presented in this study are mixed, understanding the relationship between government deficits and trade balances is crucial for policymakers in addressing the growing government debt, as well as private consumer’s confidence in domestic investment.

Introduction

Government deficits and the trade balance have seemed to fluctuate in tandem over time. This has given rise to theories connecting the two deficits to explain their relationship. U.S. fiscal deficits have ballooned in recent years, bringing renewed attention to the twin deficit hypothesis (TDH) and applying it to advanced economies. Modeling these connections is meant to explain and hopefully predict and correct future deficits, which have negative impacts on the economy through increased debt and decreased sustainable economic growth.

The TDH is the theory that both government deficits and trade balance change simultaneously and are linked. It suggests a positive relationship between the two, as deficits increase so does the trade balance. The TDH relies on Keynesian theory, where rising government borrowing drives up the real interest rate. Higher real interest rates make borrowing more expensive (leading to crowding out), causing the domestic currency to appreciate. This makes exports more expensive relative to imports, thus worsening the trade balance.

Ricardian equivalence hypothesis (REH) suggests there is no relationship between deficits and the trade balance. The REH argues consumers are forward looking, acknowledging deficit spending causing households to save more to prepare for an increase in the tax rate. An increase in the savings rate means there is no aggregate effect of deficits, therefore no substantial change in interest rates. This causal chain relies on the change in consumption of consumers.

There is mixed evidence to support either of these theories. A Granger-causality test is performed to assess the relationships between government deficits and the trade balance deficit. The United States has a complex open economy with capital flows between many foreign and domestic entities. This is a contributing factor to mixed results, as policymakers cannot rely wholly on a single aspect to correct both government deficits and the trade balance simultaneously.

Theory and Literature Review

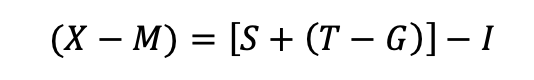

Equation (1): National Income Accounting Formula

Where (X – M) is net exports, S is private savings, T is tax revenue, G is government expenditure, (T – G) is government savings, and I is investments

The National Income Accounting formula in equation 1 can explain the basic concept of the TDH. It hypothesizes that as government expenditures increase (greater deficits) leads to a rise in the real interest rate, decreasing investments (I). This first link posits that larger deficits will crowd out private investments. Higher interest rates attract foreign capital inflows, leading to currency appreciation. A stronger domestic currency makes exports (X) relatively more expensive for foreign buyers while making imports (M) cheaper. Thus, the TDH suggests greater government deficits increase interest rates, reducing investments, which then deteriorate the trade balance because of relative global prices.

The REH purports a differing approach from the same formula. The REH assumes that because of increases in government expenditure there is a corresponding increase in private savings. There is then no crowding out effect on investments because of the change in the savings rate. Real interest rates do not increase, and the right-hand side of the formula remains unchanged, having no impact on net exports. This assumes a forward-looking consumer that anticipates increases in the tax rate, which comes from the government’s need to pay for larger deficits.

Literature is mixed determining the accuracy of either hypothesis. Most of the recent literature revolves around developing economies and Europe, leaving a gap in analysis of the United States.

Evan Lau and Tuck Cheong Tang (2009) seek to address the TDH in the United States for the period of 1970 to 2011 using a general equilibrium model. They found empirical support for the TDH through the mechanism of savings and investment channels. This study claims that a higher increase causes a decrease in both savings and investment channels. Those channels are the link that cause the currency to appreciate and the trade balance to worsen. This aligns with the TDH theory that private investment is crowded out by a rise in real interest rates. A general equilibrium model has the potential to oversimplify the interactions between variables. Their results are promising in favor of the TDH, but the current study employs higher frequency and up to date data for the United States.

Afonso et al. (2019) observes these dynamics in the Euro Area between 1995 and 2020. They used a time-varying parameter (TVP) to identify the relationship between deficits and trade balances inside the region. The study found a statistically significant effect between the twin deficits but concluded fiscal tightening at the level required to produce change in the trade deficit would have detrimental effects on the economy as whole. The short term losses potentially outweighing the long term gains from fiscal tightening. Afonso et al. signifies a relationship between these variables but also has limitations. Intra-EU trade accounts for nearly 2/3 of all European Union trade. An analysis of the European Union will be inherently more closed economy compared to the United States. This commands the need for research into the dynamics of the United States.

The THD and REH had significant traction in the 1980s. Since then, its popularity has died, but the questions they posed have remained. Literature from the beginning of this period is outdated and does not account for current financial and economic conditions, and recent data favors developing countries and the European Union.

Methodology

Data

The dataset spans roughly eleven years, from 2013 to 2024, and is for the United States. The Bureau of Fiscal Services’ monthly treasury statement is used to examine the federal deficits, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is used to determine real interest rates, and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis is used to observe the trade balance. The data is arranged monthly, spanning the entire dataset. Where only quarterly data was available, linear interpolation was used to approximate values.

The trade balance (tbalance) is measured in millions of US dollars, as well as the United States deficit. The public debt as a percentage of GDP (PPD) is measured as the monthly public debt divided by the monthly GDP and is expressed as decimal. The real interest rate was calculated by subtracting the one-year ahead expected inflation from the nominal interest rate and is expressed as a decimal. United States treasury holdings (tholding) is expressed in millions of US dollars, as well as foreign treasury holdings (FDHBFIN). United States treasury holdings and foreign treasury holdings are included by recommendation of a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study. Without these variables, this study found an inverse relationship between deficits and interest rates, which is contrary to economic theory. After inclusion of the additional variables, a positive relationship emerged and was statistically significant. Because of the increased predictive power of the additional variables, they are used here as well.

Terminology

This study employs a time-series econometric approach to investigate the TDH in the United States. It uses a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model in tandem with the Granger causality model to estimate relationships between fiscal government deficits and the trade balance.

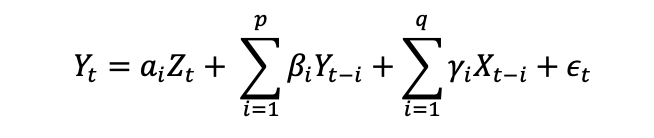

Equation (2): VAR model used in the Granger-causality Test

The above equation is for the Granger-causality test where Yt is the trade balance, Xt is the fiscal deficit, Zt is the exogenous variable, p and q are the lag lengths, a, B, y are variable coefficients, and E is the error term.

The VAR model is used to address interdependencies among multiple time-series variables. Each variable included in the model is regressed on its own past values and the other values included in the system. This test is used to determine whether past values have predictive power on each other. VAR models inherently include lagged variables, which is essential in determining relationships in this context.

The Granger test produces information on whether one variable’s time series has predictive power over another. The Granger test produces two reduced models consisting of both fiscal deficits and the trade balance to compare against the complete model containing both variables. The resulting F-statistic tests whether the addition of the dependent variable has a statistically significant effect on predicting the independent variable.

A Granger causality test is conducted within the framework of the VAR model by testing whether the lagged values of one time series significantly improve the predictive power of the series.

Model and Regression Analyses

Correlation testing was used to begin an exploratory analysis between variables. Basic linear regression models were then used to determine rudimentary relationships between fiscal deficits and the trade balance.

The VAR model used in the Granger-causality test is the preferred method because the combination utilizes predictive power in both directions for the independent variables. It also tests the effect of one time series on another, rather than using a static model. Non-lagged variables used are US treasury holdings, foreign treasury holdings, and real interest rate are included to improve predictive power.

The first VAR model and subsequent Granger test examines the government deficit’s effect on the real interest rate. This model determines the first theoretical link in the TDH. The real interest rate is regressed on the deficit as well as the PPD to ensure robustness of results.

The next VAR model and its Granger test examines the core theory of the TDH: whether the fiscal deficit has a relation to the trade balance. The PPD is again used in following deficits to ensure robust results.

Results and Discussion

Empirical Results

Table 1: Linear Regression Results

An initial Pearson correlation was conducted between both fiscal deficit and trade balance, and PPD and trade balance. The Pearson coefficient between the fiscal deficit and trade balance was determined to be -0.191, with a p-value of 0.0762, suggesting a weak, negative relationship between the two variables. The second Pearson correlation between PPD and trade balance yielded stronger results: the coefficient being -0.888 and associated p-value being 2.22e-16, suggesting a strong negative relationship between PPD and trade balance.

To examine the first connection between the debt and the real interest rate, a linear regression was run between the real interest rate, PPD, U.S. treasury holdings, and foreign treasury holdings. The coefficient on PPD is 16,481 and highly significant with a p-value of 3.16e-10, suggesting as the public debt increases real interest rates are predicted to increase.

A VAR model was developed based on the above model and the Granger test then applied. The Granger test assessing the relationship between the real interest rate and PPD yielded a Granger F-Test equaling 5.4617, and its resulting p-value was 4.47e-05, suggesting a high level of statistical significance.

The following linear regression between the trade balance and PPD, U.S. treasury holdings, foreign treasury holdings, and the real interest rate yielded a PPD coefficient of -2.657e+04. The resulting p-value observed was 0.168, signaling a statistically insignificant effect on the overall trade balance.

The Granger test from the associated VAR model derived from the above regression did not have statistical significance with a p-value of 0.459. The instantaneous test suggested a stronger relationship with a p-value of 0.0775 but still does not fall within the 5 percent threshold.

The linear regression between the trade balance and fiscal deficit, U.S. treasury, foreign treasury holdings, and the real interest rate offered additional insight. The coefficient on the deficit was 7.833e-03, with a p-value of 0.0233, which is significant at the 5% level.

The Granger test associated with the VAR model derived from the above regression also did not have statistical significance with a p-value of 0.984.

Implications and Policy Discussion

These results present mixed evidence for TDH and weak evidence for REH. The first link of the TDH is established from the VAR model and regression predicting the debts effect on real interest rates. The linear model states that as the PPD increases by one point, the real interest rate is predicted to increase by 1.582e+01 points. This satisfies the first assumption of the TDH where increased fiscal borrowing affects the real interest rates. This suggests also some level of crowding out of private investment, but further research is required to quantify those results. The REH assumes that government borrowing does not influence the real interest rate, so the findings established in the first regression present evidence refuting the validity of the REH.

This Granger test presents evidence that does not support or refute the TDH. When extending the model to predict the trade balance, statistical significance is lost. This is not necessarily surprising, as the United States is an advanced economy. It has an open economy interconnected with many different industries and world regions. The U.S. also experiences high levels of capital flows from foreign countries. This has the potential to counteract the impact of the fiscal deficit on the trade balance. While inconclusive, this study aligns with previous evidence suggesting a more complex relationship between fiscal deficits and the trade balance. Since the last major push for the TDH in the 1980s, the U.S. economy has experienced tremendous growth, changes to the level of borrowing, and differing trade dynamics. The results experienced from the study suggest there is not a simple predictor to the trade balance or the public debt in the United States. The policy implications from this finding are also relevant. There is no single variable to correcting the trade balance or fiscal deficit. At this stage, a true solution relies on acknowledging current fiscal spending and trade balance as separate entities. Trimming the trade balance requires U.S. industries to have a comparative advantage over foreign industries. The underlying relationship is therefore more complex, and further research understanding the relationship between the two deficits is needed.

The TDH presents itself to be a stronger hypothesis in closed economies or export heavy economies. More closed economies do not rely heavily on the trade balance, so changes in this metric will possibly yield stronger results. Export heavy economies are supported by their trade balance. This reliance takes up a larger share of GDP, and because of its strength supporting the country it is likely more connected to the fiscal balance. This is a potential reason why the existing literature focuses on developing countries and Europe.

Conclusion

This study uses a VAR model and Granger-causality test to determine if fiscal deficits can predict the trade balance. The model and test seek to confirm the phenomenon of the TDH and REH. The results suggest more evidence towards the TDH because of an increase in real interest rates in response to fiscal deficits, but the link to the trade balance is weak. The TDH proposes a simple relationship between the two deficits, but this study does not find explanatory power between them. Further analysis of industry specific trade balances in the U.S. has the potential to yield stronger results. Future research should focus on narrowing the scope of the U.S. trade balance to determine whether fiscal deficits impact specific industry exports.

You must be logged in to post a comment.